A partial police shutdown over unpaid wages put Rio de Janeiro on edge Friday, sparking fears of chaos similar to that seen in a neighboring Espirito Santo state where police are in revolt and criminals have run amok. Morale among street police is low as a result of nearly bankrupt Rio state’s inability to pay full wages, as well as brutal crime fighting that has seen more than 3,000 officers killed in Rio since 1994.

Police, who are classified as military, are barred by the constitution from going on strike or demonstrating. To get around that law, female relatives of officers blocked the entrances to several Rio police bases, including the elite Shock Battalion — and personnel made no effort to come out.

“We’re demonstrating to demand police get their rights back, especially security, payment of salaries on time and better equipment, not weapons that are out of order and cars that are not maintained,” said a woman outside the 6th Battalion station.

The woman, who like other protesters requested she not be identified, said her husband had been killed on duty last year. “We’ve had enough!” said another police widow helping to blockade the station. At the imposing Shock Battalion headquarters, women prevented cars and anyone in uniform from exiting.

“If you come in, we won’t let you leave,” one woman warned two thick-set policemen returning to base with rifles and other combat gear carried by Shock Battalion troopers. They politely agreed.

Police authorities said in a statement that protests were taking place outside 27 of Rio’s 100 police stations, with five reported by Globo television as blockaded. Spokesman Major Ivan Blaz told journalists that “95%” of officers were working as normal and that the state and city were secure.

The limited blockades were modeled on a broader shutdown in the neighboring state of Espirito Santo, where relatives of police closed all stations one week ago, plunging the state into chaos. Despite the dispatch of federal army troops, more than 120 people have been reported killed amid looting and robbery. Schools and bus services remained closed.

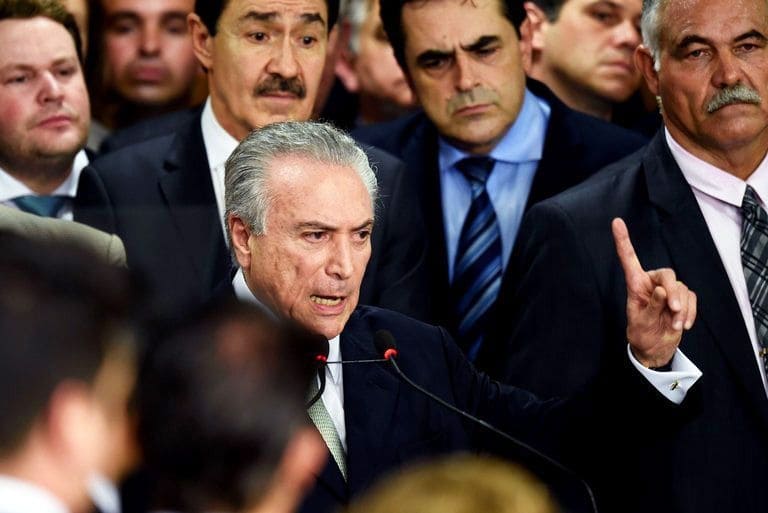

President Michel Temer, who said nothing in public about the crisis all week, called the situation “unacceptable” on Friday and said that demonstrators “cannot hold the Brazilian people hostage.”

Veja newspaper’s website quoted an unnamed high-level government source saying that 30,000 troops are on standby to respond if the police strikes spread further.

Espirito Santo police want a pay raise. In Rio, the main demands are payment of 2016’s final salary and overtime, including for working extra during the Olympic Games in August. But Rio is in dire financial straits and the corruption-plagued state is having to implement austerity measures to qualify for a federal bailout.

Given that the city is already gripped by a violent struggle between drug gangs and police, rumors that officers would refuse to work in places like Espirito Santo sent ripples of fear.

Messages widely shared on social media warned parents to keep their children out of school and to stay indoors. Newspaper front pages were filled with headlines like “Rio’s Hell” and “Rio ungoverned.”

In a video appeal, police spokesman Blaz urged officers and their families not to follow the path of Espirito Santo. “We cannot allow this scenario of barbarity to reach our houses,” he said.

However late Friday authorities in Espirito Santo said they had reached a deal to end a week-long police strike that has sparked violent anarchy dozens dead. State government officials, who had threatened striking police officers with criminal charges, said police were expected to return to work by 7 a.m. (0900 GMT) on Saturday.

It was still unclear if most policemen would stand by the deal and return to work, as the federal government dispatched more troops to the southeastern coastal state to try to quell the unrest.