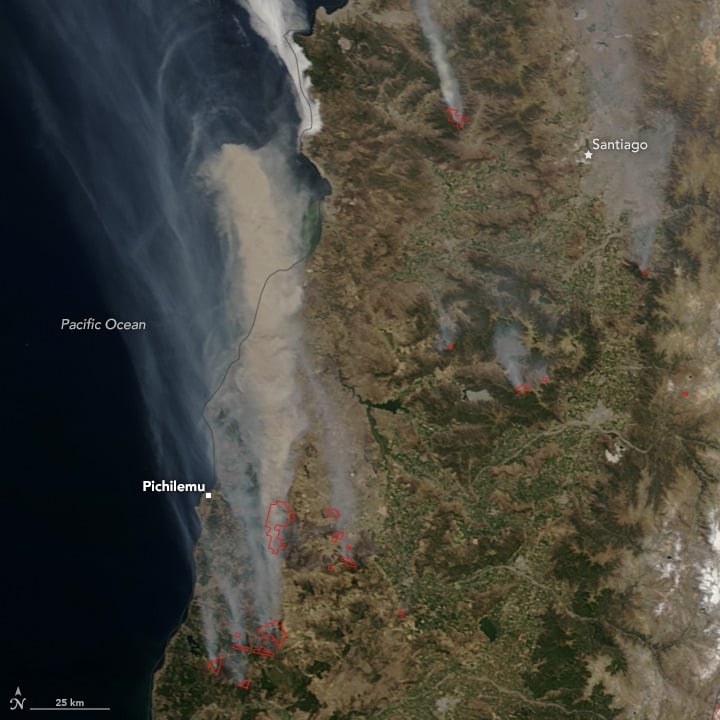

Help arrived quickly after Chile called on the international community to combat the unprecedented wildfires. Henceforth, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs regularly informed about the latest contributions, and Chancellor Heraldo Muñoz enthusiastically celebrated Chile’s popularity, which he said, came out of a “network of friendship.” The contributions were substantial indeed, and included the privately sponsored Boeing 747 SuperTanker fire engine; the Russia-sponsored Ilyushin Il-76; money aid, and numerous foreign firefighters risking their lives. The world jointly confronting Chile’s inferno looked like the liberal dream came true.

Of course, authorities should appreciate foreign support, and understandably the media relished reporting on the country’s spot in the global limelight. With all the glitz, however, the relation between fire accelerators like eucalyptus monoculture and the wood industry generally, global warming, or disappearing agriculture and Chile’s integration into the global economy remained underappreciated.

A piece in The Clinic, for example, described the relation between the wood industry and the fires. The Pinochet administration launched a corporate welfare scheme to entice super-rich families to turn wood into an export commodity that has contributed billions of dollars to the economy. Another article related how this industry impacted on the native flora by introducing eucalyptus trees. While both agree that monoculture enabled much of the fires, they ignore Brazil, where communities suffer at least since 2012 from soil depletion, loss of biodiversity and increased risks of wildfires due to eucalyptus. The dangers of eucalyptus were no secret, but Chile’s embrace of globalisation blinded the country’s leadership to take a look over the hedge. Evidently, this worked as long as Chilean-grown eucalyptus fetched high prices on the global market, but someday someone’s gotta pay up.

Playing by the rules of global capital has made Chile’s exports becoming more valuable, diminishing the difference in value between the cheap stuff going out and the expensive one coming in. But this way development economic patterns have changed. The results become visible in rural communities like Curacaví, which experience capital inflow as result of global trade, either as direct investment or in exchange for produce. Economic growth lures in foreign companies and boosts local businesses, thus raising demand for real estate causing consequent price hikes. These hikes enabled many farmers to cash in and move away from agriculture, leaving their land to urbanites and their weekend domiciles or future development projects. This way, individuals escape backbreaking work, but it also leaves the soil dry and grass growing — fertile ground for an inferno.

Adding complexity, many communities have suffered a decade-long drought, certainly related to rising global temperatures. Scientists agree that global warming arises from high carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in the atmosphere as consequence of fossil fuel burning. The more fossil fuel a country burns, however, the richer it gets. Comparing Chile and Austria using World Bank, shows that the latter with only about 7 million inhabitants, emitted 7.36 metric tons (mt) CO2/capita in 2013, generating a GDP of over US$428 billion. In that same year, Chile generated a GDP of US$277 billion and emitted 4.73 mt/capita, a sharp increase from US$77.84 billion and 3.549 mt/capita in 2003. Undoubtedly, Chile grows more efficient and wealthier, but only by increasing its carbon footprint. This contributes as much to disturbances caused by climate change, as it creates immense economic benefits stemming from commerce with the main polluters. Trade relationships aren’t innocent.

The much celebrated solidarity, moreover, entangles Chile in geopolitical complications. Russia for instance, aims to recover imperial pride via a campaign to dominate its near-abroad and hit the EU. While of tremendous help in Chile, the Ilyushin also served propaganda purposes for Moscow. Chile’s disregard for country experts — valuing their knowledge only if its serves economic purposes — could bite back when a cornered Russia poses the sanctions question. Moscow is seeking supporters, and Santiago signed up without covering its back.

Sadly, policy-makers seem to be asleep at the wheel. In January, ex-President Eduardo Frei, upon presenting his work in the Asia-Pacific, defined globalisation as a technological, not politico-economic phenomenon. Such a lazy definition allows politicians to leave Chile’s fortunes to tech corporations and regulations in other countries. But this causes damage beyond people’s eroding trust in democracy.

Fake news — propaganda — is common in Chile at least since the 1970s, when Edwards family owned publications spread lies the US government paid for. Back then, however, lies circulated in limited contexts, whereas modern technology carries fake news instantly around the world. For instance, Chilean Admiral Arancibia alleged the government knew Mapuche terrorists were responsible for the fires, but for political reasons refrained from persecuting them. Thereby he insinuated a socialist/terrorist relation that resonates well with Pinochet supporters and caters to popular anger against the government. Although the admiral backpedalled since, his claim was echoed in Wall Street Journal column of a person with a muddy reputation, but clear political agenda. Drawing up a bogeyman can damage Chile’s international standing, threaten investments, and undermine the solidarity Mr Muñoz deems rock hard.

Disengaging from the world certainly wouldn’t be a solution, but Chileans, especially the likes of Mr Frei, must appreciate that globalisation is bringing more than friends, gadgets, and sushi restaurants.