JACK BROOK

The Santiago Times Staff

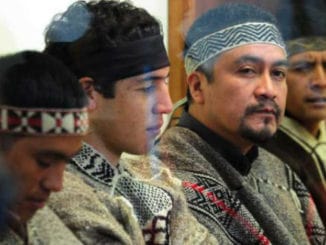

SANTIAGO – On Saturday morning of the winter solstice, the Cerro Navia Mapuche community gathered in a small grass field on the outskirts of Santiago and prepared to celebrate the coming of the Mapuche new year.

At 11 a.m., the crowd of twenty began making their way towards the center of the field as Rosa Tranamil, 60, the community’s spiritual leader or Machi, pounded out a steady and persistent beat against her kultrun. Before the ceremony, she had placed the red and white painted drum above a fire to heat the leather to produce a more distinct sound.

“The Machi plays the drum beat that connects with the rhythm of the universe and allows her to view the earth from a higher plane,” says Juan Carlos Huenchexual Chregue, 63, a Mapuche healer who helped lead the ceremony.

Activists Rally to Save Santiago’s Most Important River

Chregue wore a green and yellow headscarf with the leaves of the sacred Maqui tree tucked in the front. According to him, the leaves represent nature – the spiritual entity that the Mapuche pray to during their new year’s ceremony, known as Txeile Mapuohegun.

“As the days become longer and the sun moves closer, the spirit of the youth, like that of the trees and plants, is reborn,” Chregue says. “Today we ask a blessing for the health of our brothers and sisters and that the coming year be filled with positive energy that we may share and give back to mother Earth.”

To bless the new year, Chregue explains that the Mapuche pray before their rewe, a six-foot-tall wooden totem covered in the dried out leaves and branches of the maqui tree, and cut with jagged carvings that form spiritual steps, allowing the Machi to connect with higher powers. By praying to the rewe, Chregue says that the Machi and their community are able to invoke the Mgueiera—the Mapuche spiritual guardians of the land.

Yet the day’s celebration also underscores the Cerro Navia community’s struggle to preserve and perpetuate its traditions in an urban setting that many elders like Chregue view as a corrupting force.

Chregue learned Mapudungun, the Mapuche language, from his grandmother, along with the spiritual art of healing. However, he says that now there are less and less people with knowledge to pass forward these traditions.

“In the urban areas like Santiago, Mapuche people, especially the youth, have become distorted,” Chregue says. “We try to use ceremonies like today to plant seeds of wisdom with the children.”

According to the 2012 Chilean census, there are approximately 1,500,000 Mapuche-identifying people in Chile, or roughly ten percent of the over-all Chilean population. There are only around 200,000 people who can speak Mapudungun, with the majority located in the rural south, meaning that very few people in urban Santiago are native speakers.

President Bachelet apologizes for ‘horrors’ done to indigenous Mapuche

“There are never enough resources for the Mapuche communities here,” says the mayor of Cerro Navia, Mauro Tamayo, who briefly stopped by before the ceremony to help set up and take photos. “But we as a municipality are working to channel more support for the local Mapuche communities here.”

The lack of resources in the Cerro Navia community remains evident, however. The Cerro Navia community’s Ruka – a wooden communal gathering space – burned in a fire a few months ago and still hasn’t been reconstructed. Unlike indigenous groups in other countries, the Mapuche lack any formal sovereign territory within Chile. In urban areas like Santiago, they are forced to rely on small allotments of private land for their ceremonies.

“The Chilean state has a tremendous responsibility to recognize, respect and integrate definitely the Mapuche culture because they have been violently repressed for years,” says Karol Cariola, Member of the Chamber of Deputies of Chile, Independencia and Recoleta district. “The Chilean state should be a force for good in restoring Mapuche culture. One of its biggest challenges is integrating urban Mapuche communities in Santiago, whose ceremonial spaces are in the middle of the city.”

Under the hum of an electric power line directly overhead, the Machi and a few older women in traditional Mapuche dress – shawls and rainbow-colored headscarves with metallic circles and bird-shaped necklaces – led the procession towards the rewe. The roar of cars passed by on the adjacent road and from a nearby park the sound of reggaeton music mixed with the Machi’s drum beat.

The low throaty blast of the trutruca, a big coiled instrument vaguely resembling a french-horn with a seashell at the end, punctuated the gathering, along with the high notes of the pifilca, a small wooden flute. Both are used, according to those who play them, to help the Machi ease into her ceremonial trance.

The crowd kneeled down facing the rewe, the voices of the women quick and soft underneath, merging with the hum of the power cable, while above the murmur the slow chants of the healer and the lonko formed a prayer duet. The pitch of the prayer heightened and ebbed as the Machi raised and lowered her kultrun into the air.

Everyone present carried a piece of maqui leaf in their hand, and the chants increased as the lonko and healer planted the symbolic tree saplings in a freshly dug hole in the earth beside the rewe.

“The maqui has multiple uses: medicine, food, cloth dying” Chregue told the crowd in Spanish as he dipped the maqui leaves in water and splashed the droplets into the air, while the lonko scattered seeds into the earth.

“We can’t forget our traditions or our language,” says Hernán Huentulle, the lonko of Cerro Navia. “That’s why during the ceremony we speak in Mapudungun but also in Spanish, so that people who don’t know Mapudungun can still understand what is happening and learn from the experience. The children – and many of the adults – don’t speak our language.”

Cassandra Avello, 21, who took part in the Cerro Navia ceremony for the first time this year, says that she has started taking classes to learn Mapudungun, but that the process has been challenging. Mapudungun, a traditionally oral language, lacks a formalized alphabet. Still, Avello says that she plans to continue with the classes.

“All of the ceremonies happen in Mapudungun, and so the only way to fully integrate into the culture is to learn to speak correctly,” she says.

Rodrigo Cayún, who teaches Mapudungun, says that due to the scarcity of native speakers and state-support, there are not enough institutions or workshops for people to learn Mapuche culture, especially in Santiago. Mapudungun, Cayún adds, is not offered in the public school system. And despite a long-standing advocacy campaign, the state of Chile has not recognized Mapudungun or any other indigenous language.

“We are trying to create more dynamic ways of learning so it can be easier for people to understand and access,” Cayún says. “We are working to integrate all the communities in Santiago, trying to mobilize and prevent our language from being lost.”

However, as the prayer ceremony came to a close and the afternoon’s festivities commenced, Cayún made clear that the day presented an opportunity not to lament but to honor community and shared culture.

“I am here to be present with my people,” he said.

The prayer process continued in a chaotic synchronization that to an outsider had the appearance of a beautiful improvisation—a bugle interjecting here and there, the metal trinkets and necklaces of the women jangling with each step, and all the while the steady rhythmic pound of the Machi’s kultrun propelling the group forward.

The crowd circled, counter-clockwise, several times around the rewe. Then, they slowly retreated backwards away from the rewe until the healer halted and addressed the group.

“I’m happy to be here with all of you as we invoke the elements to bring forth the rebirth of youth, of plants, much happiness in the new year,” Chregue said, as everyone began to shake hands and hug, before congregating for lunch.

Servings of pumay – plates of steak, sausages, clams, mussels and chicken – accompanied chupilke, a red wine filled with crushed seeds.

The Machi continued to beat her kultrun, while the elder women began an informal dance.

Carmela Lucida Nulin, 69, who proudly wrapped her scarf and cloth streamers around her head in the red, gold, blue and green colors of the Mapuche flag, smiled as she stepped backwards and forwards in synch with the beat of the universe.

“I am content right now to be around my rewe, reunite with the mother Earth, and celebrate.”