ALI DASHTI

The Santiago Times Staff

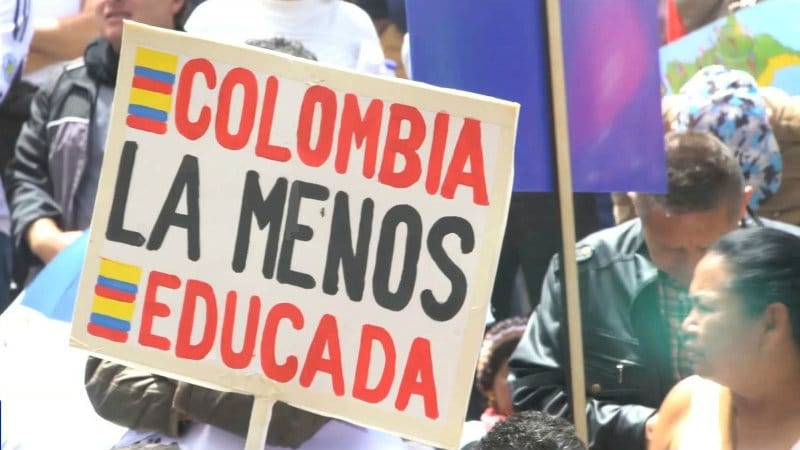

BOGOTÁ – On May 11, millions of Colombian teachers took to the streets all across this South American country to demand better infrastructure, higher salaries and implementation of 2015 agreement.

The strike was called by Colombian Federation of Educators, FECODE in Spanish, the largest and most organized worker unions in Colombia. The national strike, which affected more than eight million students in the country for more than one month, was lifted on five days later when the government of President Juan Manuel Santos and the union announced they reached a new agreement.

Demands and Challenges

“Our strike was in defense of quality public education that is accessible to all,” says Ana Victoria Gomez, a young Colombian teacher who joined the ranks of her compatriots in the strike that lasted 37 days.

She rejects the government claim that Colombian teachers were solely asking for higher salaries and says that was only one of a numerous reasons why millions of teachers quit working for more than a month.

“We took to streets to ask that the government invest more in education, to ask for better infrastructure and an end to the rampant corruption,” adds the 31-year-old teacher from Colombia’s Boyacá Department, north east of the capital Bogotá.

The government of Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos claims it has invested in education far more than any other previous governments but teachers say they don’t see any real improvement in either the infrastructure or the quality.

“Nothing more than a business”

One of the bones of contention was and continues to be the government-funded School Meal Program (PAE in Spanish) that provides free lunch to students in all public schools. The program has come under fierce criticism and scrutiny as many schools have not received any meals.

Ana Victoria, who has been working seven years in a public school, also criticizes the project and says the meal students at her school receive is very poor in nutrition and can’t even be called “proper meal”. “In many schools, like mine, kids only get milk, juice and some biscuits. Is this meal? Do you call this lunch?” She asks me rhetorically.

Former Education Minister Gina Parody, who is rumored to be standing for president in next year’s elections, has heavily criticized the School Meal Program, saying it’s fallen into the hands of mafia.

Franklin RobledoMosquera, another teacher from the Department of Chocó, one of Colombia´s poorest regions, says the School Meal Program is very essential to the implementation of extensive school hours, a project called JornadaUnica in his country. However, he mentions that his school has not benefited from the state-provided meals and in some cases have been very poor in quality.

Chocó, which sits right on both the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean coastlines, is rich in natural resources, however long periods of battles between Colombia’s FARC rebels and government forces as well as poor management have left the region at the mercy of lack of proper governance and a corruption haven.

Diana LisethPallaresSarabia, another Colombian teacher who has been working 5 years in the country’s public education system, riles the program as well and says it has turned into a “business” for a small group of companies that are filling their own pockets by providing very meager meal for millions of students.

Poor Infrastructure

The 33-year-old Diana believes the government must first of all improve the educational installations in each region before launching the long school hours also known as JornadaÚnica. She says many schools don’t even have water. “There is no water in my school neither for drinking nor for bathrooms,” says the young teacher who works in a rural school in Colombia’s volatile Santander region right on the border with Venezuela.

Diana says her school doesn’t have the necessary equipment to make it look like a proper school and that students feel comfortable.

Franklin says Colombia’s Education Ministry gave the school hundreds of tablets last year but there is no internet there making these technological devices nearly of no use.

This 55-old year teacher says teachers don’t have their own desk in classes and need to be standing all the time. “Students in my school they fight over chairs. There aren’t enough chairs for everyone.”

“It’s even a bigger problem when it rains because the classes are flooded,” goes on Franklin.

Ana Victoria also says that classes at her school, located in a remote part of Boyacá department, are crammed with 40 students and when it gets hot, there is no ventilation. “It’s not what either we or the students deserve in this country,” stresses Ana Victoria.

“We have neither drinking water nor water to be used in bathrooms. When it rains, we can’t teach because classes are flooded. Students in my school fight over chairs as there aren’t enough ones for every single student.”

Last-Year Salaries

Ana and many of millions of other Colombian teachers went on a national strike two years ago in 2015 and went back to schools after a deal reached with the government. One of the main points of that agreement was that government will increase teachers’ salary according to the inflation rate. She acknowledges that government made good on that promise but highlights that they hadn’t seen the same change this year.

“Value-Added Tax has risen to 19% but my salary has not risen even a peso,” mentions Ana Victoria.

“We are the best professionals in this country but the worst-paid ones,” adds Franklin from Chocó.

According to the newly-reached agreement, the government has agreed to increase teachers’ salary based on the terms of 2015 deal.